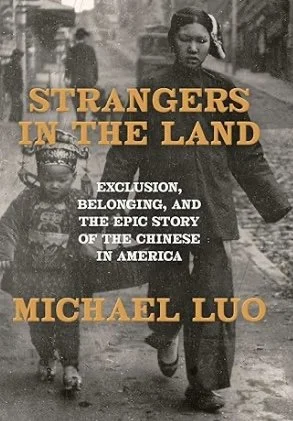

Strangers in the Land by Michael Luo (Penguin Random House) ~Janet Brown

Expulsion. Detention centers. Separation of children from their parents. Battles over birthright citizenship. Legislation banning immigration. Vilification of targeted ethnicities. 2025? No. This happened at the end of the 19th century and well into the 20th, directed at what we now call the “Model Minority.” The parallels between that time and our own are as horrifying as they are ignored.

The end of the Civil War in 1865 that brought a stop to slavery in the U.S. gave rise to a labor crisis and a demand for cheap labor. Households needed servants, mines and factories needed workers, and the most difficult portion of the transcontinental railway was yet to be built. In parts of the nation where slaves were not in use, immigration provided essential workers who would work more cheaply than native citizens, and while the East Coast was the entryway for European immigrants, San Francisco was the gateway for the Chinese.

The first recorded Chinese arrival to that city was in 1848. Within two years there were 800 Chinese and by 1852, the number of arrivals from China that disembarked in San Francisco swelled to over 20,000, which was deemed “a frightening number.”

However these immigrants were almost all male, looking for work, and were found to be “as efficient as white laborers.” While Irish workers were apt to strike for higher pay, the Chinese didn’t and for that they faced retaliation. The first expulsion of Chinese labor from a mine site took place in 1849 and over the years this happened repeatedly and violently. Houses were set on fire, lynchings took place, and vigilante mobs assaulted and murdered Chinese workers with impunity, joined by the Ku Klux Klan under the guise of “The Order of Caucasians.” Cities in the Pacific Northwest fell prey to vigilantism with a three-day spree of violence driving out Chinese residents in Tacoma and mobs in Seattle forcing residents of Chinatown onto waiting ships, leaving a “small contingent” within the city.

With a smaller number of Chinese arrivals, the East Coast had to bring Chinese workers from San Francisco to serve as strike breakers and to staff factories. When immigration battles were waged in Congress, it was Easterners against the West, with the lawmakers who defended Chinese rights coming from eastern states with smaller Chinese populations. The Chinatown in New York City grew along with a professional class that became politically active, while in San Francisco a detention shed that served as an immigration station was a national disgrace for twelve years.

Michael Luo, an editor at the New Yorker, has painstakingly given an overview of the Chinese presence in America, an account that dwells as heavily upon battles among U.S lawmakers as it does upon the bigotry and violence that assailed Chinese, no matter what their immigration status might be. His account is vivid and detailed, but he gives this history a staccato presentation rather than a linear one. By focusing on issues thematically rather than as an ordered number of events, he brings an element of confusion that is daunting to the average reader, who will find themselves wishing for a timeline. He ignores the history of the Chinese in places other than San Francisco and New York, except for the massacre in Rock Springs, Wyoming and the expulsions in Tacoma and Seattle, while the Chinese migration from the Southwest into Mexico is nowhere to be seen. Still this mammoth accomplishment is important, relevant, and needs to be read.