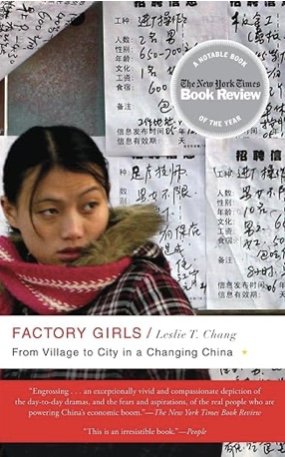

Factory Girls by Leslie T. Chang (Random House)

In 1978 a Taiwan manufacturer established the Taiwan Handbag Factory in an isolated corner of Guangdong Province. It was the only foreign factory to have come to the small town of Dongguan, a place without railway connections or roads. It hired local labor but soon needed to augment that supply with migrant labor from rural China. Two years later Deng Xaoping established the first of China’s Special Economic Zones in Shenzhen, fifty miles from Dongguan.

By the 1990s, Dongguan had become a manufacturing hub, with factories for electronics and computer parts standing beside the ones that made toys, clothing and shoes. It became famous for its “factories and prostitution,” a city “built for machines, not people.” Instead of streets, it boasted ten-lane highways.

In 2004, Leslie T. Chang, a bilingual reporter for the Wall Street Journal, came to Dongguan. Her goal was to report on migrant labor in that city, a tsunami of workers who had been streaming to its factories for two decades. She stayed in Dongguan for 1-2 weeks every month for two years.

A young woman herself, who is fluent in Chinese, Chang found it easy to gain the confidence of young women who worked in the factories, who at that time made up 70% of the labor force and one-third of the migratory flow. Homeless until marriage, by virtue of their gender these girls were never considered permanent parts of their family households. When parents realized their daughters could become financial assets in factory towns, they encouraged the girls to take that leap.

Chang follows the lives of two girls, Min who left home at 16 and Chunming who came to Dongguan when she was just a year older. Through them she chronicles the progress that could be made by girls who have left their villages.

Although social pressure may have sent these girls to work in factories, what keeps them there is freedom and mobility. If they dislike their workplace, they change jobs, going to “talent markets,” places where job fairs meet speed dating. Rapid-fire interviews are conducted to find workers who are “female, pretty, and single,” the younger and the taller the better. Lies and subterfuge are common, girls who have lost their identity cards and procured another go by a new name for as long as that’s necessary. Men are less desirable job candidates in this fast-paced employment arena and are usually confined to maintenance positions, while young women find their way into office jobs.

Within a year, Chunming goes from making 300 yuan a month to 1500. Min, after having her identity card, mobile phone, and her money stolen from her, goes from living on the streets to “building a new life from scratch,” getting a job in a Hong Kong-owned handbag factory where her salary is high enough to make her the dominant figure in her rural family.

Factory girls are the leaders of a social revolution. The money they bring to their parents give them a position of power. At the Lunar New Year, they are the ones who present envelopes of money to their elders and household decisions rest with them. As they gain positions of status in the workplace, they often outrank the men they date and use that power to their advantage. Chunming’s stock phrase when finding a man didn’t measure up to her standards is “Let’s just be friends, then,” which she often pronounces in a matter of minutes.

Pragmatic and ambitious, these girls set personal goals that dominate their time away from their jobs. Chunming keeps a diary and studies Ben Franklin’s Thirteen Rules of Morality. When direct sales come to China, promising a route to prosperity, speaking skills are a path to success and young women flock to classes that give them that ability. English is so in demand that the Taiwan-owned Yue Yuen plant that manufactured Nike, Adidas, and Reebok, offers English classes onsite at their gated facility, a place that also has a kindergarten, a movie theater, and a hospital.

Girls who had come from small farms find they need polish to achieve success and attend “academies” that tell them how to dress, eat, smile, pour tea, use the telephone, and when it was necessary, how to drink. (“Do you know how to make cocktails?” one of Chunming’s friends asks Chang.)

Chang wrote Factory Girls twenty years ago. It prompts a deep curiosity about what became of these upwardly-mobile, ambitious young women and if their effect on society continues to hold its power. A sequel is screaming to be written, if only to continue the stories of those indomitable girls, Min and Chunming. ~Janet Brown