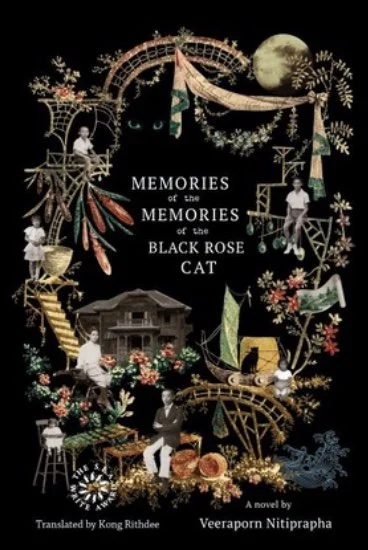

Memories of the Memories of the Black Rose Cat by Veeraporn Nittiprapha, translated by Kong Rithdee (River Books)

Memories of memories, we all have them--stories of when we were small, told to us so often that they become a real and vivid part of our remembered pasts; events we’ve invented, so certain they occurred that they become embedded as false memories; tales about great-grandparents whom we never met but whose exploits are part of our own pantheon of stories that we tell and retell.

Memory is a realm of evanescence, highly prized and easily lost. It’s the province of ghosts, spiderwebs, soap bubbles. A story emerges, shimmers, and vanishes, crowded out by many others. Which is real? Which is fantasy?

This is the world where fiction was first invented. This is the world that comes alive in all of its gleaming spirals in Memories of the Memories of the Black Rose Cat.

Thai author Veeraporn Nitiprapha was brought to the attention of western readers when Kong Rithdee translated her first novel, The Blind Earthworm in the Labyrinth, into English. Several years later Rithdee has done it again, translating Nitiprapha’s lapidary magic realism while never sacrificing the distinctive flavor of Thai storytelling.

This novel begins slowly with the pace of a tropical afternoon when a boy named Dao explores “a melange of tattered, warped memories,” ones he thinks perhaps were never his own but were given to him by someone else. His world is one of stories told to him by a grandmother who has disappeared from a house where he lives with his mother, a woman whose presence is spectral. Only when he enters the Rain Room does he ever see anyone else, a girl within a large mirror who looks oddly familiar to this boy who has never left his house and has never met a stranger.

Dao is a vessel for memories. He’s the last of what was meant to be a family dynasty, begun by Tong, a man from China whose body is covered with “black freckles like lightless stars…burnt-out constellations.” Tong’s success in his adopted country makes it possible for him to buy the big house near a pond covered with pink lotus blossoms, next to a forest of acacia trees that fill the air with blankets of yellow pollen. Through his house Tong’s children come and go, leaving only their stories behind.

Truth and lies, success and failure, and the curse of death by water--none of Tong’s children lead happy lives, nor does the generation that follows them. The memories of the family are anchored by history and suffused with poetry. Their stories float through the house and into Dao’s mind like curls of smoke, defying linear rules of time or place. Not until the final pages of the novel is there a shadowy explanation, offered just after the shocking acts of violence that precede Dao’s existence.

Nitiprapha has the gift that made Virginia Woolf famous, one that lets her bend time to her own uses without sacrificing her story. Although Woolf and Garcia Marquez both come to mind while reading her novel, the world Nitiprapha creates is vividly and viscerally Thai. The history, the food, the ghosts, the lingering image-filled descriptions all provide entry points to a place that lives in the memories of memories, fading fast, seen in a blink of time before dissolving into “a fragment of deep longing.”~Janet Brown