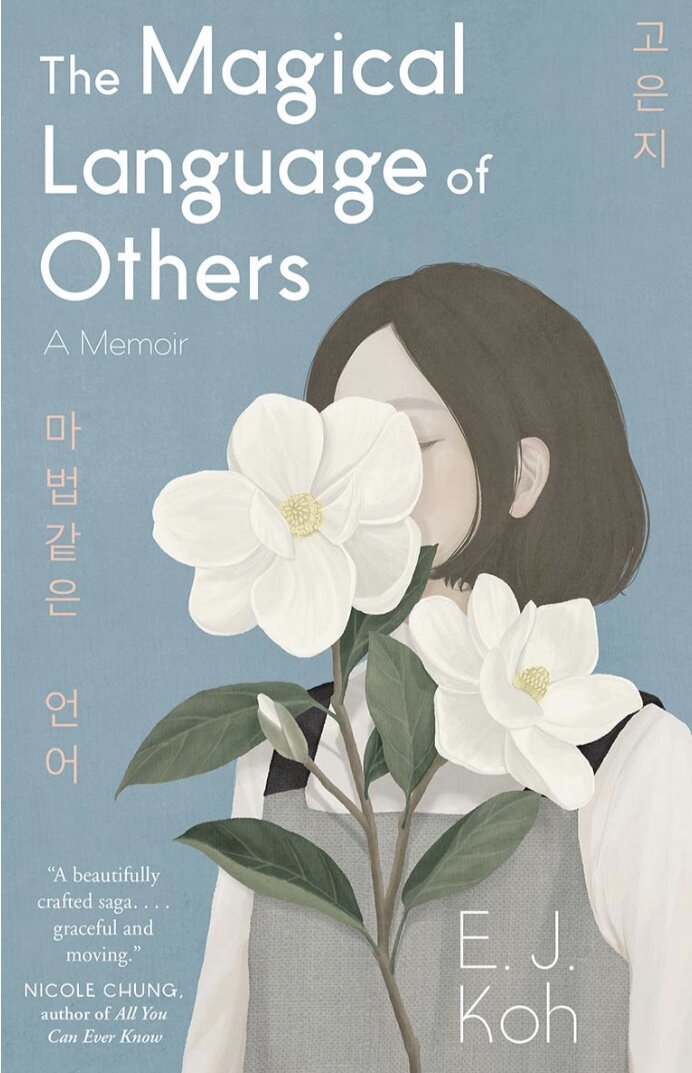

The Magical Language of Others by E.J. Koh (Tin House Books)

Eun Ji Koh, California-born with Korean parents, is steeped in different languages from the very beginning of her life. Her father’s mother, who cared for her when she was small, came from Korea but had been born in Japan and lived there for her first decade. Although Koh hears her grandmother speak Japanese when they’re at a Japanese shopping center, she herself learns only a smattering of words in that language; her grandmother wants to “secure me with English.” Much later, long after that grandmother died, Koh learns from a DNA test that she herself is part Japanese, a fact to which her parents claim ignorance, speculating that perhaps this came from “a violence we didn’t know about.” But Koh, even before discovering this part of her heritage, plunges into total immersion at an international language program in Japan. At seventeen, she absorbs Japanese as though she’s trying to reclaim the grandmother who loved her. By the end of the summer, her teacher is in tears. “Who will talk to you in Japanese again...you will look for it everywhere, anywhere you go. Your hunger will teach you what you’ve lost.”

But Koh has already learned the language of loss and hunger, cloaked in letters written in Korean, the simple version that’s all she understands. When she is fourteen, her father takes a high-paying job in Seoul. He finds a comfortable house for his children to live in and then flies away with his wife, believing “it was better to pay for your children than to stay with them.” Koh, who just recently has entered adolescence is now under the care of her nineteen-year-old brother. Her parents would not return to the US. for seven years.

Every week Koh’s mother sends her a letter, using the Korean that she hopes her daughter will understand, “kiddie diction,” flecked with bits of English to help clarify her messages. They veer from the maternal to the childlike and in them Koh is addressed as a daughter and as her mother’s parent, reflecting the “Korean belief that you are born the parent of the one you hurt most.” Koh’s way of delivering pain is silence. Although she speaks to her mother on the phone, she never replies to these letters.

In college at a poetry workshop, Koh discovers another language. On her second class she hands her teacher forty poems that she had written the night before, poetry about her mother. Her teacher responds with “I wish I could do that,” and then after reading them, “There’s no magnanimity.” Another poet tells her to be “relentlessly forgiving...choose love” in her poetry and in acquiring this new language, Koh’s life takes on a deeper dimension. She learns the “difference between having a life and being a life.” She translates her mother’s letters into English, faces the truth of her abandonment, and then faces her parents when they finally return to the U.S.

Koh’s poetry breaches the surface of her memoir in stunning sentences and her blazing honesty vouchsafes details that are both painful and evocative. This is a book that will break hearts and then put them back together, piece by piece.

“Languages, as they open you, can also allow you to close,” Koh says. In this beautiful book, she proves that language can also reopen its users after it has closed them, and lead them into gleaming new landscapes of pleasure and clarity.~Janet Brown