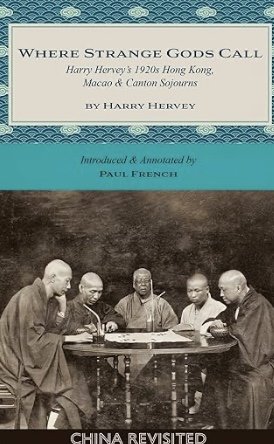

Where Strange Gods Call: Harry Hervey's 1920s Hong Kong, Macau and Canton Sojourns (Blacksmith Books)

Before Fu Manchu, the Dragon Lady, the Yellow Peril, and the benign cliche of Charlie Chan, there was Harry Hervey. A young prodigy who published his first piece of pulp fiction when he was sixteen and whose stories were frequently found in Black Mask magazine after his early debut, Hervey published his first novel at the age of 22. Caravans by Night: A Romance of India was followed a year later by The Black Parrot: A Tale of the Golden Chersonese and apparently gave Hervey a financial windfall that took him to the part of the world that he had profitably imagined.

In 1923, Hervey voyages to Hong Kong where he immediately begins his search for corners of that city that would be “rich in the atmosphere of Cathay.” Fortunately for him, he has a local contact, a wealthy, cultured Hong Kong resident whom he had met in New York. Chang Yuan becomes Hervey’s guide and mentor, giving him an introduction to “a race that had always seemed inscrutable to me.” Together the two explore the “nauseous effluvia” and “fetid gloom” of Chinese opera theaters, the “gorgeous wickedness” of Macau’s gambling halls, and make the acquaintance of the “queer, impassive little dolls” who sing in restaurants as wealthy gentlemen have their suppers. “It was inevitable,” Hervey says, “that we should visit an opium house,” a place he finds “as colorless as naked lust.”

In between these forays into the parts of Hong Kong that Hervey finds “very wicked and very pleasant,” Chang Yuan delivers interminable lectures on Chinese history and politics. These are so meticulously recorded that it becomes impossible to believe they’re not the puerile thoughts of Hervey himself. This theory is almost confirmed when Hervey describes Chang as “uncommunicative,” which would preclude his monologues that take up many of the pages in his Hong Kong chapters.

Without Chang Yuan’s companionship, Hervey seems daunted by Canton, which he describes as “too stupendous and too indefinite to be sheathed in words.” He certainly doesn’t explore it with the enthralled energy shown by Constance Gordon-Cumming, forty-four years earlier. However he has a focus for this visit. Fascinated by Sun Yat Sen from childhood, he manages to gain an audience with his hero, whom he terms the Doctor of Canton, a man whose “personality submerged words.” The words recorded by Hervey speak of the threats posed by Europe and Japan and of the “militarists of the North (who) wish to Prussianize China.” The interview ends with Sun Yat Sen declaring the necessities of having only one currency and one language shared by all Chinese, which Hervey later dismisses as “splendid dreams.”

This reprint of two chapters from Hervey’s Where Strange Gods Call: Pages Out of the East seems a peculiar choice for Blacksmith Book’s new series, China Revisited. Hervey’s writing can barely qualify as travel writing, steeped as it is in his fictional fantasies and thinly veiled racism. “How pleasant I was (sic) to see soldiers who were not yellow,” he gushes when passing a group of British troopers and Chang Yuan is described as “astonishingly well educated…faintly grandiose.” Not even his childhood idol escapes the snobbery of this high school-educated product of Texas, who charitably reports Sun Yat Sen’s perfect enunciation “was not surprising, as he is a college graduate.” It escapes Hervey that even the sing-song girl who entertained him with a song in Pidgin English is bilingual, which he himself, in true American fashion, probably is not.

Perhaps when all of the choices for this series of attractive little books are published, Harry Hervey, who later became a Hollywood screenwriter largely because of his presumed knowledge of Asia, will take his place among them without making readers wondering why. Let’s hope so.~Janet Brown