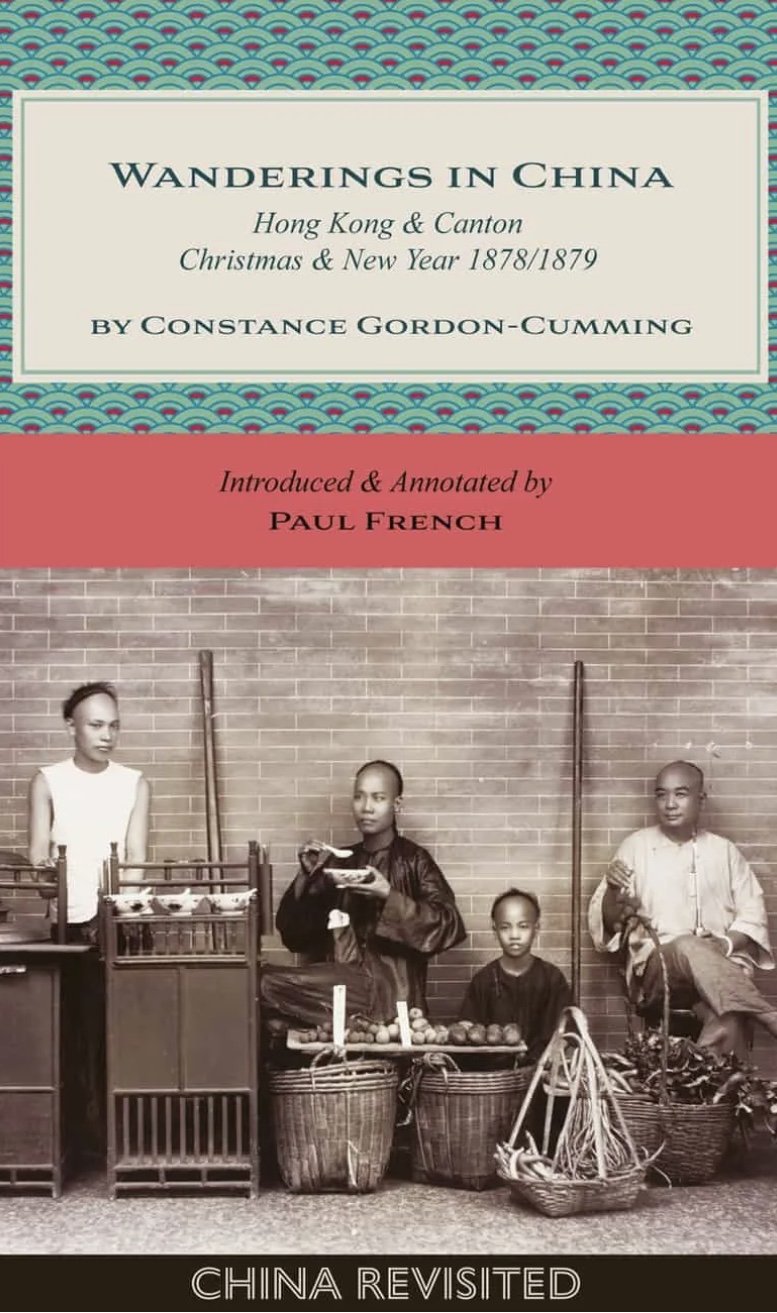

Wanderings in China: Hong Kong and Canton, Christmas and New Year 1878-1879 by Constance Gordon-Cumming (Blacksmith Books)

Constance Gordon-Cumming was in her fifties when she first came to Hong Kong on Christmas Day in 1878 but her reactions to this city, and later to Canton, had the enthusiasm of a young girl who had just left home for the first time.

This was far from the case. Gordon-Cumming had been a devoted traveler for twenty years, making her first overseas voyage when she entered her thirties and sailed to visit her sister in India. From there she had gone to Ceylon, Fiji, New Zealand, and Japan before she had set her sights upon China. Although at this point she had seen enough of the world to view it with a jaded vision, this wasn’t her style. An artist who had the goal of ending “never a day without at least one careful-colored sketch,” she looked at the world with hungry eyes that took note of everything she saw.

Gordon-Cumming fell in love with Hong Kong’s “steep streets of stairs” that led past “luxurious houses encircled by “camellias and roses and scarlet poinsettias.” Bamboo groves and banyan trees, the intertwining of the city’s Chinese and Portuguese areas, the piercing blue water of the surrounding harbor—”Only think what a paradise for an artist!”

Paradise went up in flames that night when Christmas festivities were interrupted by an act of arson that threatened to consume the city. Perched above the conflagration in a Mid-Level home, Gordon-Cumming watched the fire as it destroyed Chinatown and advanced upon the affluent homes of Hong Kong’s expatriates. Ten acres of the city were devastated with 400 houses gone in a single night, an unimaginable spectacle with “a horrible sort of attraction…so awful and yet so wonderfully beautiful.”

By New Year’s Day, Hong Kong’s “social treadmill” had resumed and by January 9th a short voyage takes Gordon-Cumming to Canton. There she’s met by a “resplendent palanquin” that was fit for a mandarin but lay in wait to take her to her hostess on the Western enclave of Shamian Island. Delighted by the English social life that held sway in this community, she refuses to succumb to its charms that keeps many foreign residents of Shamian from going into the heart of Canton.

Instead Gordon-Cumming submerses herself in the city’s shops and markets, on streets with names that are “touchingly allegorical”—The Street of Refreshing Breezes, The Street of One Thousand Grandsons. She’s overwhelmed by the commerce that she finds there—flowering branches for Chinese New Year, oranges that have been peeled because the peels, used for medicine, are more valuable than the fruit, ivory carvers, tallow-chandlers, vendors that sell drinking water next to porters that transport raw sewage. (Tea drinking is the pervasive custom because the water for it has been boiled, she observes.)

From there she is taken to Canton’s riverine world where a separate city exists. Families live in domestic comfort on boats, with order preserved by “water police” who are notoriously corrupt. Crafts that hold barbershops and medical clinics serve this community, along with market boats and river-borne kitchens. Floating biers carry corpses to their final destination while other vessels hold leper colonies. Gordon-Cumming, with aplomb befitting the daughter of a British baronet, finds her way to the “flower boats” that she euphemistically describes as places where dinner parties are attended by wealthy citizens who are entertained by “singing-women.”

From Canton she travels to Macau, a place she finds “most fascinating” but so “essentially un-Chinese that I have decided to omit the letters referring to it.” This decision does quite a bit to illuminate Gordon-Cumming’s character and helps to explain the decision that ended her life of travel. A year after her time in Canton, she remained aboard a ship that evacuated its passengers when it ran aground. Refusing to leave the watercolors she had painted on the voyage, she stayed with the captain until the two of them were finally brought to safety.

Did her explorations come to an end because she was unnerved by this disaster or was she blacklisted by shipping companies because she refused to take to the lifeboats when that command was given? Somehow I doubt that this conclusion to her travels was Gordon-Cumming’s idea and I’m sure she fumed over it for the rest of her life.~Janet Brown