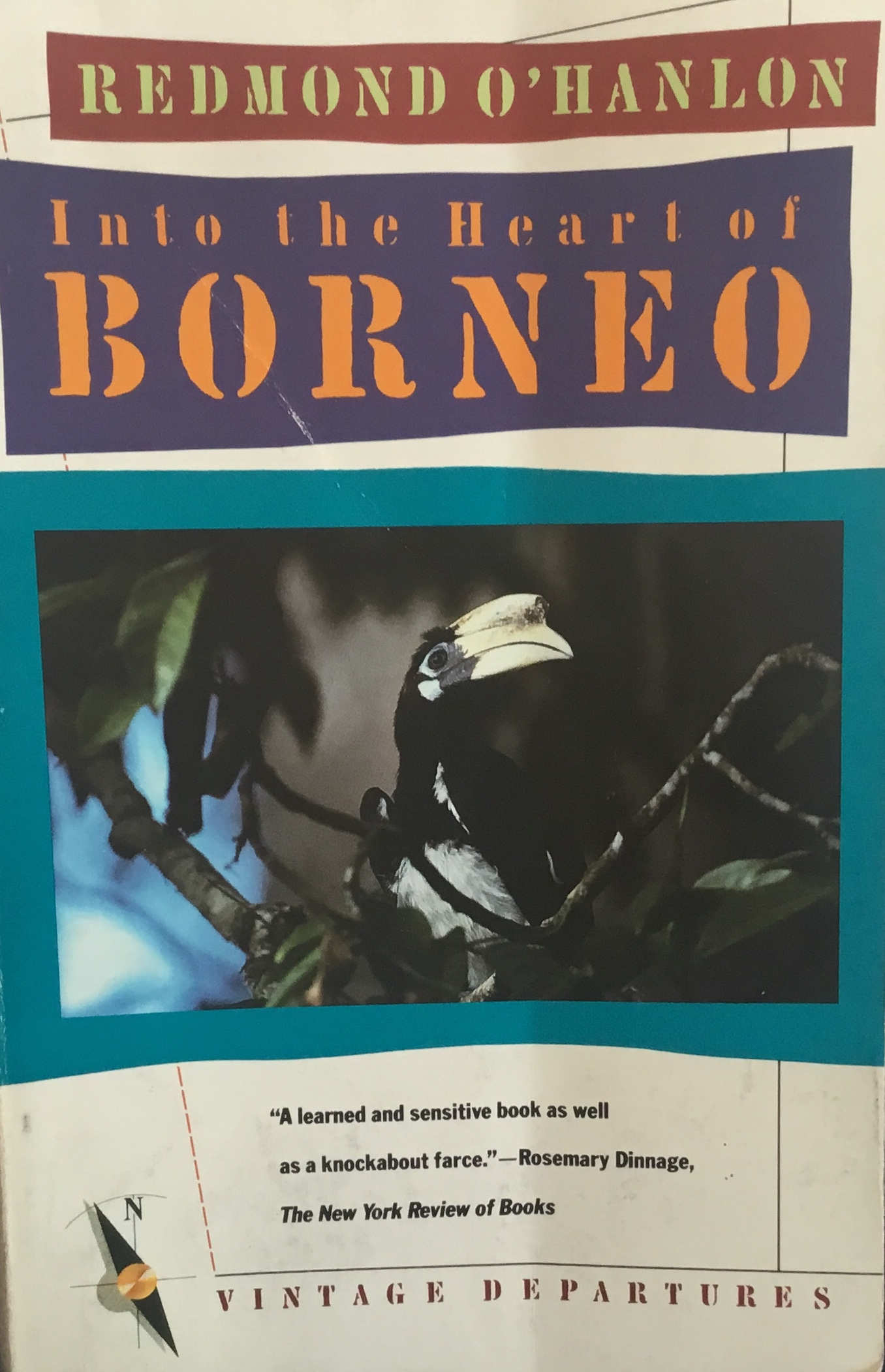

Into the Heart of Borneo by Redmond O'Hanlon (Vintage Departures)

Two middle-aged British academics embarking upon a journey up a jungle river on the island of Borneo--what could possibly go wrong? After all, Redmond O’Hanlon has a relative who once trained men in the art of jungle warfare and his chosen travel companion, the poet James Fenton, spent time in Cambodia, Vietnam, South Korea, and the Philippines as a journalist. Armed with an impressive library of natural history and poetry, a survival kit supplied by the British Special Air Services, and a rather terrifying amount of information given by the Major in Charge of SAS Training, Fenton and O’Hanlon fly off in search of the rare two-tusked Borneo rhinoceros, while carefully observing all avian wildlife that might come their way.

“I want permission to go up the Baleh to its headwaters and then to climb Mount Tiban,” O’Hanlon announces to a skeptical Malaysian bureaucrat, “James Fenton and I wish to re-discover the Borneo rhinoceros.” Somehow they manage to gain the necessary permits and the guiding services of three Iban, members of a jungle tribe who were once famed for their skill in headhunting and who have never been to the area that they will help their charges to reach.

Spending their days in a boat and their nights in campsites on the riverbanks, O’Hanlon and Fenton swiftly learn that they are comic relief for their companions. The Englishmen come with flyfishing gear that is inferior to the harpoons of the Iban, they are rapidly laid low by the arak that their guides can drink by the quart with few ill effects, and are less than charmed by the steady diet of rice, bony river fish, and meat from an occasional turtle or lizard. Elephant ants and leeches are plentiful; every morning the novice explorers coat themselves with SAS anti-fungal powder, and Fenton comes close to drowning in the whirlpool of a waterfall. All of this provides rich amusement to the Iban, who are delighted to offer their new friends as entertainment to the jungle tribes they encounter along the way. Yet the exploration party all develop an understanding and respect for each other that ripens into true friendship.

Underpinning a wildly funny narrative of Oxford men struggling through Borneo is a stunning naturalist’s view of tropical wilderness and its fauna, with an underpinning of accounts from past explorers. Gibbons, langurs, kingfishers, and eagles are marvels that make up for the agonizing discomforts of jungle travel. And although the elusive Borneo rhinoceros never makes an appearance, O’Hanlon ends his quest by meeting one of the men who have caused that animal to become a rare and miraculous sight.

Not just a diverting travel narrative, Into the Heart of Borneo gives a poignant look at a way of life that is already beginning to vanish in 1983, as timber interests discover the jungle. O’Hanlon’s journey could never be replicated today. Below the wit and charm of his story lurks a bitter sadness that surfaces when it’s read in this century. The world he found and learned to love is rapidly disappearing, if not destroyed. ~Janet Brown