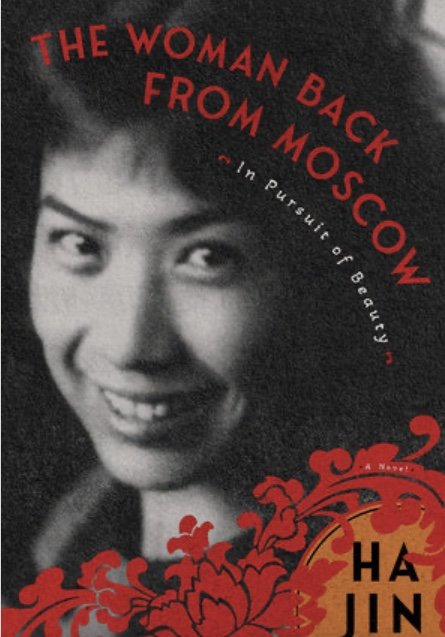

The Woman Back from Moscow by Ha Jin (Other Press)

Yan’an, 1938: Two young women study dramatic arts in the place where Mao Zedong brews the ideas that will lead to China’s liberation in ten more years. Both women have recently appeared on stage, with Yomei in the starring role and Jiang Ching taking a secondary part. The older of the two by seven years, Jiang Ching, is ambitious and competitive. Yomei at seventeen is an incandescent beauty, glowing with life and in love with the theater.

The older woman’s jealousy is apparent but Yomei is under Zhou Enlai’s guardianship and knows she has nothing to fear. The daughter of a dead revolutionary, Yomei became Zhou’s adopted daughter when she and her mother moved to Yan’an. Already powerful, Zhou’s cloak of invulnerability shelters the girl he has taken into his family, leading people to call Yomei The Red Princess.

The community of rebels in Yan’an is small and closely knit. While Mao is a man whom Yomei is familiar with, Jiang Chang has to work to gain his attention. Yomei receives Mao’s permission to study drama in Moscow for seven years while Jiang Chang uses every advantage she possesses to become Mao’s indispensable helper and eventually his wife.

When Yomei returns to Yan’an after struggling to survive in Russia during World War II, she has turned from acting to become a director. Steeped in seven years of theater arts training in Russia, where Stanislavsky has transformed the way plays are interpreted, Yomei has soaked up everything that her teachers could give her. Her intelligence allows her to enter into the heart of every play she directs and her enthusiasm and generous way of teaching others makes her a charismatic figure. Combining that with her fluency in Russian, her sophistication from her years in another country, her relationship with Zhao Enlai and his wife, and her glowing beauty, she is irresistible.

Jiang Chang, on the other hand, has become Madame Mao, China’s First Lady. She’s eager to use Yomei to her own advantage but Yomei has learned to be wary of politics. Seeing that Jiang Chang plans to use culture and the arts to increase her own power, Yomei keeps her distance.

Ha Jin has taken the life of Sun Weishi while giving her the name she called herself when she wrote letters to close friends and family, Yomei. “Reality,” he says, “is often more fantastic than fiction.” His research to uncover the truth in Yomei’s story carried him only so far, There were gaps in her life that he was forced to create, rather than recreate, so he calls this work a novel instead of a biography.

As he carries Yomei through seven hundred pages, he brings her to life as an artist who had the power to enchant everyone she met, except for the woman whose goal was to “crush her spirit and destroy her beauty.” Slowly Ha Jin uncovers the politics that led to the horror of the Cultural Revolution and the insane power of the woman who brought it into being. What was at first the story of art and beauty becomes an inexorable tragedy of power and twisted political decisions that darkens the second half of this novel, as it does Yomei’s life.

Born In China in 1956, Ha Jin was a child during the Cultural Revolution and its tragic consequences. He came to the U.S. as a student of American literature in 1985 and made his decision to stay after the Tiananmen Massacre. A poet and a novelist, he writes his poems in Chinese and his novels in English.

In a book as lengthy as The Woman Back from Moscow, this is both an advantage and a handicap, especially when he writes dialogue, where his language becomes stilted. However, this slight lapse in facility simply accentuates the Chinese reality of the thoughts and words and actions that spawned terrible forces and engulfed the life of a brilliant and beautiful artist.~Janet Brown