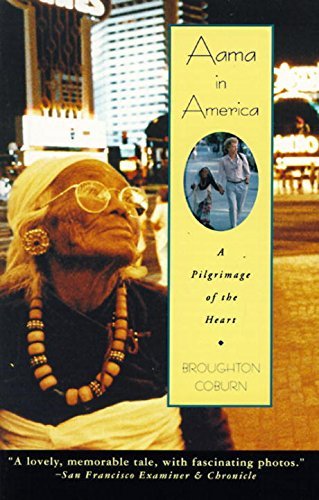

Aama in America : A Pilgrimage of the Heart by Broughton Coburn (Anchor Books)

Vishnu Maya Garung is an eighty-four-year-old Gurung woman from Nepal. Everyone in her village calls her Aama which is the Nepali word for “mother”. Author Broughton Coburn lived and worked in Nepal and the Himalayas for nearly twenty years. First he was a Peace Corp volunteer teacher, then an overseer for rural development and wildlife conservation projects for the United Nations and other agencies.

It was when Coburn lived in Nepal as a teacher that he met Vishnu Maya Garung (Aama). When he met her, Aama was a widow in her seventies. Coburn moved into a loft above a water buffalo shed that she owned. Aama became his landlady, and from these humble beginnings a friendship would form. Aama treated Coburn like her own son. Coburn says she saw him as a “dharma son, the male offspring she had never given birth to, sent from the heavens by the deities to be spiritually adopted”. Coburn immediately felt a close bond to Aama as he had recently lost his own mother.

He wrote a book about living with Aama and working and traveling with her throughout Nepal. The book was titled Nepali Aama : Portrait of a Nepalese Hill Woman, originally published by Moon Travel Handbooks in 1991. A new version was published in 2000 by Nirmal Kumar Khan with the subtitle being changed to Life Lessons of a Himalayan Woman.

While working in Nepal, Coburn met a woman from the U.S. who had been working in the country for more than ten years before they met. They soon dated and became a couple. After living together for four years, they decided to travel the U.S. together to see if they were as compatible as they had been while living in Nepal. However, Coburn wanted to see one more person before leaving the country.

It had been two years since Coburn visited Aama. He went to see her with his girlfriend Didi in tow. Didi was well aware of Coburn’s relationship with Aama and was looking forward to meeting this woman who was well into her mid-eighties by now. When Aama saw Didi, she said to Broughton, “You’ve brought me a daughter-in-law”.

Relieved at finding Aama still alive and healthy, on an impulse, Broughton said, “Aama, how would you like to go to America with us?”. Aama’s only daughter, Sun Maya is the first to react. She looks at the two foreigners and just laughs, imagining her eighty-four year old mother in a land where she wouldn’t know anybody or speak the language. Even Didi thinks they should discuss it further.

Aama surprises all of them by answering, “Why wouldn’t I want to go? Why wouldn’t I want to see my dharma son’s and daughter-in-law’s home and meet their relatives?” And with those words, the preparation of taking Aama to the U.S. begins.

Their travels throughout the U.S. results in Aama in America. The three unlikely travel companions spend time in Seattle, Washington—the start of their twenty-state tour of America. Aama is very spiritual and often questions why Americans don’t worship any deities or say prayers for their good fortune.

With every natural wonder she sees—the redwood trees in California, the Pacific Ocean, the famous geyser, Old Faithful in Yellowstone National Park, she feels awed and makes a prayer for each place. Coburn and Didi also take her to the “World’s Happiest Place”— Disneyland.

Every experience Aama has—the places she sees, the people she meets, things we take for granted, are all given special attention. At times she’s humorous and at times a bit frustrating as Coburn and Didi are often scolded about their lack of spirituality.

While mostly a travel journal of an extraordinary trip, Aama in America is also a very spiritual narrative. As the subtitle suggests, it really is A Pilgrimage of the Heart. However, this pilgrimage isn’t only made by Aama, it’s also a pilgrimage for the author himself who still has unresolved issues concerning his mother’s death, his relationship with Didi, and of course his bond with Aama. The trip may have been an unforgettable journey for Aama . It’s also a story you will not likely forget. ~Ernie Hoyt